Through a New Lens: The 1960 Debates.

The 1960 televised debates between presidential candidates Richard Nixon and John Kennedy changed the course of the campaign, sealed the deal for Kennedy, and changed how American’s view candidates. Though presidential candidates had public encounters and intraparty debates on radio and television before September 1960, the Kennedy-Nixon debates were the first nationally televised debates hosting the major party nominees. Television had become central to American culture through the 1950s. By 1960, 88 percent of homes had a TV.

The television networks and candidates planned for a spectacular event and set some ground rules. The sponsors convinced Congress to modify the equal time rule, so they wouldn’t have to include the 14 lesser-known candidates, and offered $2 million of free air time.

Both Kennedy and Nixon served in WW II. Both were first elected to Congress in 1946. Nixon, the Republican, had served the last eight years as Eisenhower’s vice president, Kennedy, the Democrat served in the US Senate. The election was going to be close and these proposed debates could determine the winner.

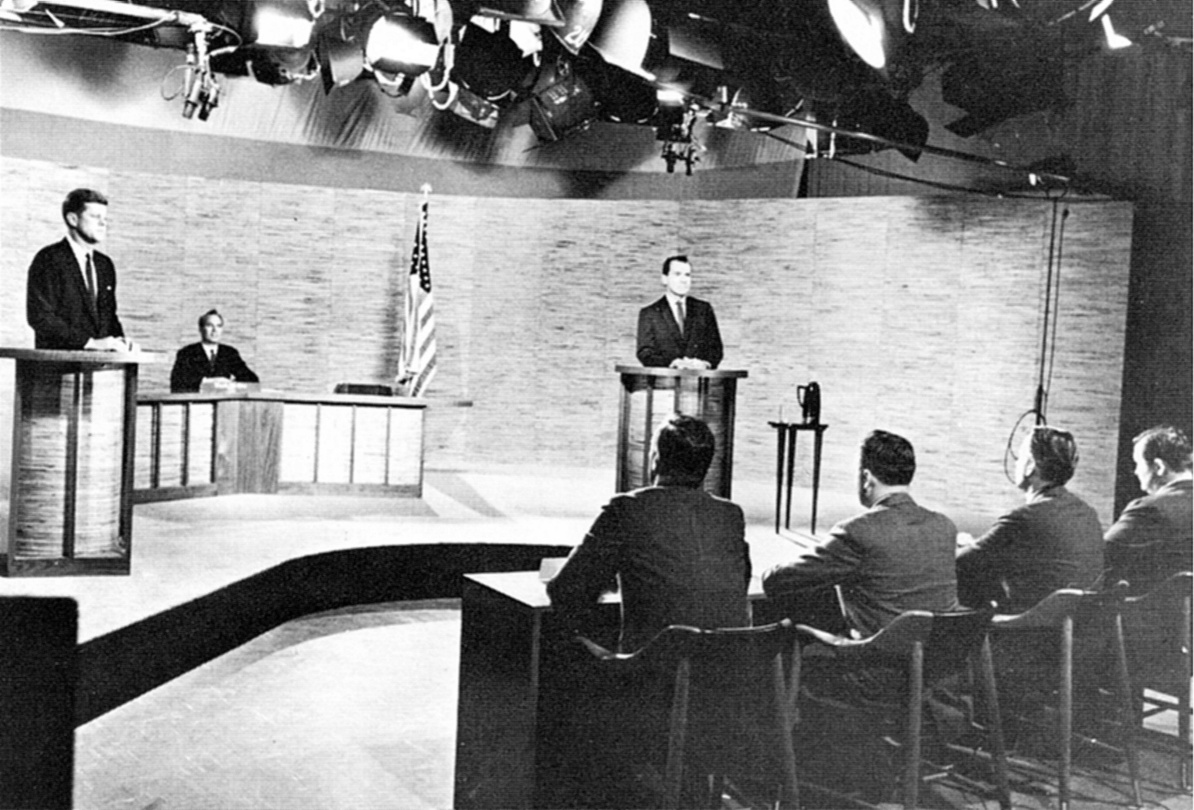

The candidates’ surrogates met in New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in early September to discuss the terms and rules. They agreed to a series of four, one-hour appearances to be aired on all major TV and radio networks. They also decided on no notes, safeguard dignity, eight-minute opening statements, and two-and one half minute responses to questions. All four debates took place in silent studios, not before any citizen audiences. The first took place in Chicago.

The two men took starkly different paths toward the first encounter. Nixon spent two weeks in the hospital after injuring and infecting his knee. Leaving the hospital, he began an intense campaign schedule. He covered 25 states in the two weeks between his release and the debate. When he arrived to Chicago, Nixon was ten pounds underweight. “My collar was now a full size too large, and it hung loosely around my neck,” Nixon recalled. He banged his same recovering knee when getting out of the car. The Kennedy team arrived with a foot locker of files and an Ivy League team to prep the senator. Kennedy was able to take a long nap between study sessions and relaxed on his hotel’s sun deck. On the way to the debate Kennedy said he felt like a prizefighter preparing for a world heavyweight match. One aide replied, “No, Senator, it’s more like the opening-day pitcher in the World Series—because you have to win four of these.”

Howard K. Smith moderated the first debate on September 26, 1960. No questions or topics were cleared ahead of time. The career broadcast journalist recalls, “Having the two appear live, side by side, answering the same questions was a welcome innovation.” But Smith says it was not much of a debate because “the reporters on the panel were not allowed to ask follow up questions, both candidates shamelessly slid by questions rather than answer them.”

Nixon wore a light suit that blended into the background. JFK wore a dark suit that made him stand out in crisp contrasts. In addition to the differences in the candidates’ physical appearances, they differed in their demeanor and how they debated. Kennedy’s sentences were short and sharp. He spoke to the people through the lens, Nixon debated his opponent. Nixon looked tired and kept offering white papers for clarification. Reporter Theodore White summed it up, “The vice president, by contrast, was tense, almost frightened, at turns glowering and, occasionally haggard-looking to the point of sickness.” Even Nixon’s mother called him to find if anything was wrong because he did not look well.

Three more debates followed, but a strong impression had been made on the US electorate. Those listening to the debate on radio thought the candidates pretty even, while those who viewed it on TV sided with Kennedy. Nixon did well in debate number three where he answered questions from Los Angeles and Kennedy from New York, but Kennedy appeared better in the others.

The race was close and probably could have gone either way. In fact it was the closest in the popular vote ever. These debates made JFK’s victory certain. “Those who claim [the debates] were the decisive turning point in the 1960 campaign overstate the case,” Nixon later claimed in his Memoirs. “To ascribe defeat or victory to a single factor in such a close contest is at best guesswork and oversimplification.” Yet a host of experts view the debates as the obvious turning point in the campaign that changed public perception of both men. One survey at the time concluded, “Kennedy did not necessarily win the debates, but Nixon lost them.”

JFK’s performance solidified Democratic support, which had been unenthusiastic since his nomination. Southern Democratic governors watched the debate at a conference and sent Kennedy a telegram of congratulations.  With such an endorsement came the reliable Democratic machines of the South. And, according to Kennedy advisor Ted Sorenson, people no longer saw Kennedy as a Catholic.

With such an endorsement came the reliable Democratic machines of the South. And, according to Kennedy advisor Ted Sorenson, people no longer saw Kennedy as a Catholic.

By one reliable mark, Kennedy outscored Nixon by close to 20 points in every debate but the third one, which Nixon won 42 to 39. Elmo Roper revealed a more telling statistic: 57 percent of voters believed the TV debates influenced their decisions and 4 million ascribed their final voting decision to the debates alone. Of those 4 million, 72 percent voted for Kennedy and only 26 for Nixon. Since he won by a mere 112,000 votes nationwide, JFK was justified in saying a week after the election, “It was TV more than anything else that turned the tide.”