The 1800 Presidential Election.

The 1800 presidential election was a tight race amid intense partisan politics. With no clear winner, Federalists and Republicans in the US House of Representatives balloted to select the new president in what appeared a deadly atmosphere. In the aftermath, Americans re-evaluated the electoral process, and the losing candidate avenged his loss by killing a statesman who campaigned against him.

Presidential electors met in their respective state capitals on December 3, 1800 to choose from incumbent President John Adams, Vice President Thomas Jefferson, New York statesman Aaron Burr, and South Carolina Senator Charles Pinckney. National politics were fiercely divided among the Federalists and Jeffersonian-Republicans. When the sealed electoral votes finally arrived to the US Senate on February 11, Jefferson, serving as President of the Senate, counted the votes. Jefferson and Burr both received 73, while Adams received 65 and Pinckney got 64.

With no clear winner, the House had to decide between Jefferson and Burr. Republican party regulars, if there was such a thing in 1801, favored Jefferson. Federalists from the other camp favored Burr as the lesser of two political evils.

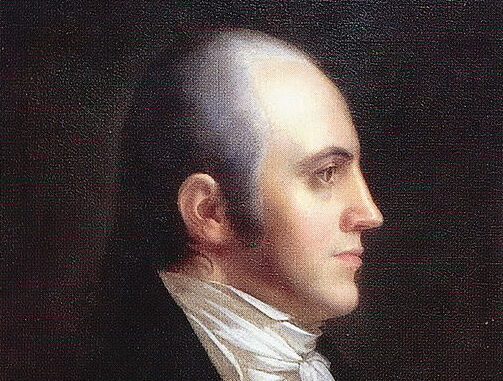

Influential Federalist Alexander Hamilton now had to decide between his chief rival Jefferson and a fellow New Yorker he never trusted. Realizing the options, Hamilton opened the way for Jefferson and smeared Burr. He told fellow Federalists the party would be “signing their own death warrant” if they endorsed Burr. “He is bankrupt beyond redemption, except by the plunder of the country.” As the House election drew near, he called Burr “the most unfit man in the US for the office of President” and the “most dangerous man of the community.”

The political conflict brought violence and danger, some rumored, some real. Reports surfaced of a Federalist conspiracy to assassinate Jefferson. Others heard Federalists had commandeered military arms from local militia units to reclaim the government by force if they lost the election. Two Federalist House members received anonymous death threats if they did not vote according to the will of the people in their states. The Republican governor of Pennsylvania promised to send the state militia to the capital to arrest any congressman who named someone other than Jefferson or Burr as president.

The House began balloting to determine the next commander in chief. Under the Constitution, each state casts one vote, by delegation. With 16 states in the Union at the time, nine votes constituted a majority. On the first ballot Jefferson won eight states. Burr received six, mostly from New England. Maryland and Vermont had evenly mixed delegations and were deadlocked.

Jefferson was one vote away from the presidency. Into the dinner hour, the House conducted its sixteenth round of voting. Not once had the vote changed. Representatives recessed for dinner at the boarding houses and taverns in the new national seat of government. They resumed discussions and balloting until casting their nineteenth ballot at three in the morning. Nothing had changed. Over the next few days, the House met and voted several more times, still deadlocked.

Delaware’s lone House member, James Bayard, held more power in his hand than any other. Bayard, a faithful Federalist, had corresponded with Hamilton. Bayard had voted for Burr every time, but could swing the election to Jefferson by switching his vote, or simply by not voting, giving Jefferson eight out of then-15 states, a decisive majority. Author John Ferling suggests Bayard approached a Jefferson ally to strike a deal before changing his vote. Bayard wanted to assure that Jefferson, as president, would accept Federalists’ terms that Hamilton had earlier articulated: support public credit and the US bank system, maintain and enhance the navy, and keep Federalists in appointed offices.

When a Federalist caucus learned of Bayard’s offer, they called him a traitor. Congressman Samuel Smith of Maryland confirmed to Bayard that he’d talked to Jefferson and as president he would honor these requests. In Bayard’s mind the deal was made unless Burr could offer the party something more.

Bayard soon learned that Burr was “determined not to shackle himself with federal principles.” On February 17, the House gathered at noon and cast the 36th ballot with no vote from Delaware. Federalists from Maryland, Vermont, and South Carolina also abstained, giving Jefferson a total of ten votes and Burr only four.

Bayard and others confirmed later that Jefferson agreed to his opponents’ demands. Jefferson denied such a political bargain, though he acted in a way that confirms such a pledge—he did not fire or replace Federalists nor did he touch the US bank. Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow says Jefferson probably owed his victory to Hamilton as much as any other politician.

Political divisions continued, but Jefferson tried to calm tensions in his inaugural address, claiming “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” Burr did not respond in kind. After Hamilton leveled another anti-Burr campaign against him during his quest for governor of New York, Burr challenged him to a duel and killed him.